The United Church of Canada Archives holds a significant collection of records which document the church’s colonizing practices across hospitals, missions, day schools, and residential schools. Since 2022, the United Church’s General Council Archives has been undertaking a large digitization project focused on making these records more accessible to Indigenous survivors and communities.

Growing out of the archives’ response to the Truth and Reconciliation (TRC) Calls to Action (2015) and our commitment to implementing the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP), the project is the third in a three-phased research project. This third phase involves the review, description, and digitization of records to facilitate a greater understanding of the Archives’ Indigenous materials and easier access to this information by Indigenous communities. The General Council Archives are carrying out this project in collaboration with a third-party vendor who will undertake the bulk of scanning.

As the General Council Archives Digitization Assistant, the review, description, and preparation of materials for the digitization project encompasses the bulk of my work. In this post, I’ll share a behind-the-scenes look at the processes involved in digitization.

Acknowledging positionality

The digitization project reconciles with the church’s colonial legacy. While engaged in work related to the harm done onto Indigenous people by the settler-colonial mission, I believe it is key to recognize my own positionality as a settler. As Indigenous Studies professors Eve Tuck and K. Wayne Yang note in their essay, “Decolonization is not a metaphor,” conscientization is not enough in unsettling colonial realities: critical consciousness must spur divestment. As decolonization implicates us all, I situate my work within the restoration, restitution, and repatriation work needed to assist Indigenous mechanisms of re-dress.

Reviewing materials

Reviewing archival textual records is a vital step in the digitization process as it ensures relevant materials are prepared for digitization, metadata is recorded, and any conservation risks are identified and recorded.

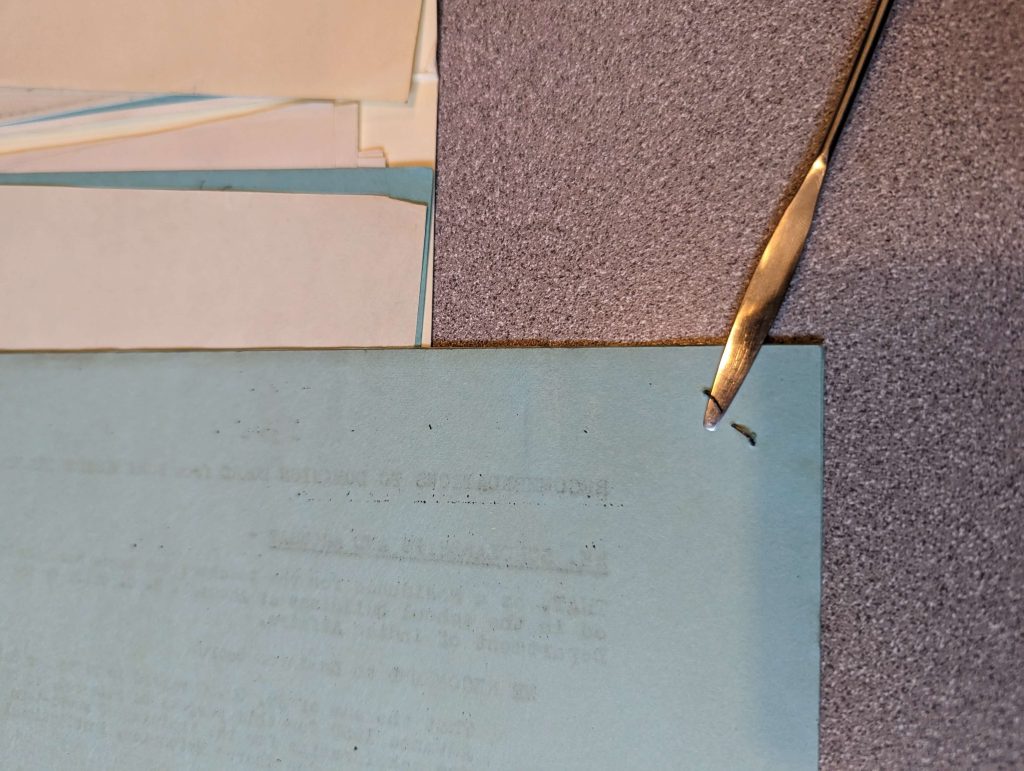

During the review stage, we also remove all staples and paperclips so the records are ready for scanning. A micro spatula comes in handy during this process!

During the review stage, we also remove all staples and paperclips so the records are ready for scanning. A micro spatula comes in handy during this process!

Unlike the archival textual, periodicals are not reviewed for digitization but rather, to improve access. Collecting metadata pertaining to relevant materials is necessary for ascertaining articles related to missions, hospitals, and day schools which were not inventoried during the TRC.

Barriers and considerations

The General Council Archives’ holdings of textual materials exceeds one million pages. The sheer volume of materials involved in the project calls for a strategic approach. Prioritizing materials that cannot be digitized inhouse ensures these records can be made more easily accessible through digital surrogates in the near future. Prioritizing ledgers within each fonds also folds into this reasoning.

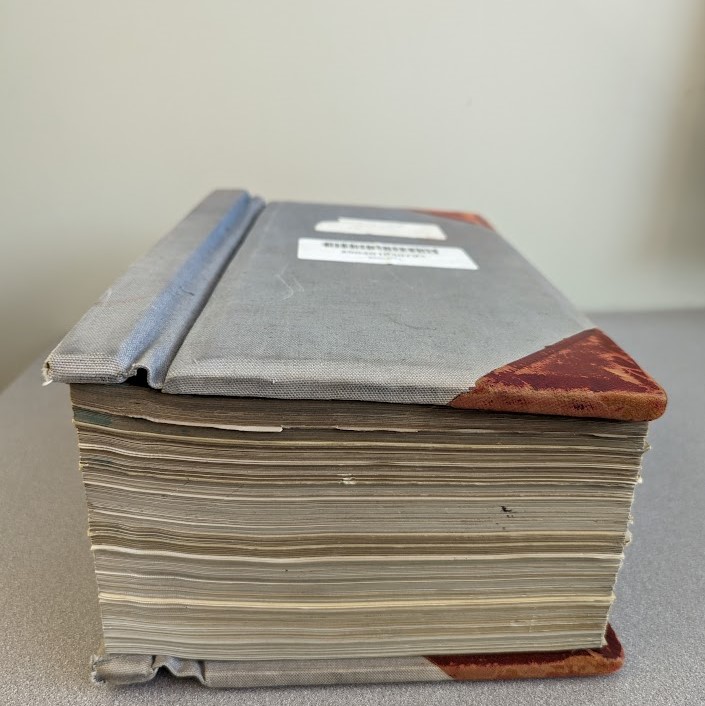

By “ledgers”, we refer to any bound volume included in the project’s scope. The wide range of materials constituting ledgers include agendas, copybooks, financial records, and more. Many of these records include material not relevant to the project but the high informative value of the material that is pertinent requires a deep review of each and every page.

Ledgers, such as this oversized volume, can contain comprehensive information spanning several decades.

Ledgers, such as this oversized volume, can contain comprehensive information spanning several decades.

The process of reviewing these materials can take time. A bound volume can contain up to 4000 pages. Illegibility can also be a concern for both handwritten and typewritten text. In some cases, it may just be a matter of acclimating to a record creator’s particular writing style but for others, text may have faded due to photodegradation. Binding issues may also be a concern for some particularly fragile records, in which case digitization must be weighed alongside preservation concerns. Oversized materials may require some ingenuity in figuring out the best plan-of-action in rendering a digital representation that best captures an impression of the physical object. Recording this information is key to maintaining the transparency of the project and addressing any issues ahead of sending records to our digitization partner for scanning.

Collecting and crosswalking metadata

A major priority during the review stage is the collection of metadata (“data about data”). While these records are associated with finding aids with high-level descriptions, the metadata collected for the project offers additional detail regarding institutions and First Nations communities invoked. A consideration of record subjects can be important in better accounting for the complex narratives emerging from the written record. A fuller metadata framework helps differentiate thousands of pages of information into clear, searchable information.

Crosswalking metadata is an important step following the initial collection process. This need touches upon the harmful language and ideologies present in many of the church’s colonizing records. The archival record may contain names that do not reflect recognized institutions or communities. “Crosswalking” this metadata is translating these elements to reflect a different standard. By linking records to current used terms and names, the archives can better share records with affected communities today.

Managing digital surrogates

Once records have either been scanned in-house or received from our digitization partner, the files themselves must be maintained akin to the physical records themselves. I emphasize these digital files as surrogates as they act as counterparts to the original records and provide valuable information but cannot replace the original record altogether. That said, the digital file is wrapped in its own technical specifications and capabilities. With access top of mind, reviewing digital materials for quality control is necessary to ensuring records have an enduring accessibility.

Conclusion

Important work continues on the digitization project. Our progress can be tracked on our regularly updated timeline.